How To Fix A Cracked Turtle

Ron Hines DVM PhD

More Complex Turtle / Tortoise Shell Repair Procedures

More Complex Turtle / Tortoise Shell Repair Procedures

All Of Dr. Hines’ Other Wildlife Rehab Articles

All Of Dr. Hines’ Other Wildlife Rehab Articles

Orphaned wildlife tend to knock more than once at the doors of kind-hearted people. So for baby cottontail rabbits go here, for opossums, here & here, raccoons, here, squirrels here & here. The care of bobcats and other toothy large creatures are best left to professionals, for them go here.

Below You Can Read In Detail How That Was Done:

Please don’t be intimidated by the number of surgical instruments and products I use when repairing these little guys. Good jobs can be done with simple craft tools. Eighty percent of the tools I use are donated by mobile surgical instrument repair services and hospitals in my area.These people are generally thrilled that items they had planned to discarded have a chance for a second life. The occasional donations I receive pay for the rest.

Turtles and tortoises have remarkable powers to recover from shell accidents when given a little assistance. Good outcomes give a lot of cheer to wildlife rehabilitators who have to deal with so many animal injuries that have no cure. That is because broken wings, arms and legs can rarely be restored to the 100% efficiency demanded in the wild. But many turtle and tortoises with severe shell fractures, when given proper attention and a period of rest and recovery do just fine.

Far and away the greatest two threat to these shelled creatures are habitat destruction and automobiles. Turtles and tortoises are slow – giving multiple vehicles opportunity to run over them. Near misses don’t spur them on. They just lead to prolonged periods of withdrawal into their shells and more time to get run over.

This article concerns the shell fractures I see most frequently. It does not concern multiple shell injuries that result in substantial missing portions of the shell – or severe fractures with internal injuries like these:

One has to question whether attempting to repair the more severely injured turtles and tortoises is a kind thing to do. Despite initial “success” (looking good after repair), no one has ever studied how long those animals live after release or the pain that they endure. Predators and starvation weed out animals that are not 100% fit. And with time, large patches tend to come loose or trap infections in water-dwelling turtles. I personally believe that it is more humane to put them down. When heavy vehicles pass over a turtle or tortoise, internal organs like the liver get crushed. The shell may return to a near-normal shape after the vehicle passes. But repairing the shells of those internally injured animals does not repair their more serious internal issues. For the rest of this article, I use “turtle” for tortoise unless something applies only to tortoises.

Here Are Some Important Things To Keep In Mind:

First off – Turtles And Tortoises Bite.

They bite hard, and they can reach farther back toward your fingers than you might suppose. They also carry salmonella. Wash your hands after every encounter with a turtle or with the contents of an aquarium that contained one. Children should not consider them toys. If you have chronic health issues yourself, consider if you really want that exposure.

Does This Turtle Or Tortoise Weigh Less Than It Should?

Tortoises and turtles on the move due to habitat destruction and stress often stop eating and lose weight. Many develop respiratory tract mycoplasma infections. Their nostrils are often plugged or appear smaller than they should be. When you pick up those animals, there is little weight to them other than their shells and skeleton. None of these turtles have done well for me when they experience a shell fracture as wandering tortoises often do. These are some gopher tortoises that were brought to me already ill due to habitat destruction in Florida. Gopher tortoises are very territorial and protective of their turf. So, they cannot be kept together as they are in this photo for more than a very short time:

Fractured Turtles Are Often More Severely Injured Than First Meets The Eye

As I already mentioned, the body organs of cracked turtles have sometimes been severely compressed. That can result in issues that are considerably more important than their cracked shells. Does the turtle have blood, liquid or air bubbles coming out its nose or out of the crack? Is there a foul odor? Do all of its feet function normally? Withdrawal from a toe pinch is not sufficient to confirm that the turtle’s leg has feeling – you need to observe synchronized leg movements. Are the turtle’s eyes bright or are they sunken from dehydration? Although egg laying and normal wandering can be the stimulus for an overland trip of a female water turtle, so can poor water conditions in its pond.

Cracks (fractures) in the carapace (upper shell) are usually apparent. But it is very common for a hairline crack to also be present where the carapace attaches to their lower shell (plastron):

Repair

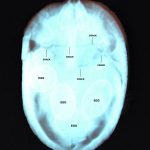

Passing a Q-tip saturated with 3% hydrogen peroxide over the shell causes tiny cracks to bubble and foam – a good way to discover, confirm and sanitize them. Rehab facilities with financial resources greater than I currently have can sometimes see those cracks better on x-rays than with the naked eye: (photos are not of the same turtle)

Hydrogen Peroxide is also helpful in detecting fly maggots in any open wounds. It stimulates them to come to the surface after which they can be plucked out with tweezers. Swabbing peroxide or organic iodine solutions rather than poring or dribbling them into wounds of uncertain depth prevents those liquids from entering the body cavity itself. You do not want that to happen. Few of you reading this article have access to the facilities necessary for an in-depth turtle health work up. But should you, a turtle’s health exam can be just as detailed as an ER examination for you.

Be Hygienic And Clean When Working With Injured Animals

There is no need to dress like an operating room surgeon during shell repair but cleanliness is a must. Turtles in nature are considerably more contaminated with bacteria than you and I are and no amount of scrubbing will change that. It will just remove the outer protective waxy layers of its shell. These are cold-blooded reptiles with their own unique bacterial flora. Turtles, like all reptiles, have an immune system and body defenses against infection that are quite unlike yours or mine. They rely on compounds like beta-defensin, which tend to localize infections and prevent them from spreading throughout the creature’s body (become “systemic”) and on their innate immune system (non-specific immune system) which is considerably more robust than those of warm-blooded creatures. A turtle or tortoises’ immune system is also active at lower temperatures than the immune system of mammals. (read here) The downside of their more primitive immune system and that of birds is that cheese-like (caseous) lumps tend to form in the infected areas that are not eliminated through drainage like pus is in mammals. This material has to be manually scooped out to allow the healing process to complete. Another problem is that this cheesy material has little or no blood circulation within it. So, antibiotics have a tough time killing any bacteria or fungi that dwell within the material.

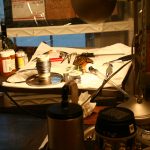

When I sterilize clean stainless-steel wires, drill bits and surgical instruments I use in this procedure, I do so through “flaming” with a butane cigarette lighter such as the one pictured in this photo:

The Shell:

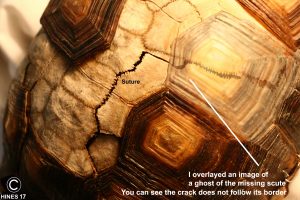

Most folks know that the shells of turtles and tortoises are made up of smaller organized bony sections covered with a thin fingernail-like keratin coating (the scutes). These bony sections are connected to each other through fine, saw-like borders called sutures. What many folks don’t realize is that cracks generally follow the margins of these sutures – not the margins of the outer scutes.

That needs to be taken into account when deciding where to drill holes meant to keep broken shell portions in as close a proximity as possible, so they will heal. If the sections are brought together well, they should fit together like the halves of a lover’s locket. To not tear out when the cracks are drawn together, the holes need to be drilled considerably back from the edge because turtle shell is somewhat fragile, being made up of “foamy/spongy” cancellous bone – with voids and chambers.

How Fast Do Turtles & Tortoises Heal?

Not all turtles of the same size and species are going to heal shell fractures at the same rate. When they eventually do heal, they do so by a slower process than mammals. (read here) The season of the year, temperature and a prior life in stressful conditions all influence healing rates and abilities. A poor environment also a stimulates turtles and tortoises to migrate – so your particular turtle may have been stressed and not in the best of health before it was run over. That also plays into your decision as to whether it would be wise for you to return the turtle or tortoise to the same body of water or woods from which it came.

The Law

Some states, have strict rules that tortoises must be returned to the exact location where they were originally found. (e.g. Texas, Florida). That is because they fear that relocated tortoises might spread the respiratory mycoplasma disease that I previously mentioned to uninfected tortoise populations. The organism responsible is Mycoplasma agassizii. (read about that here) Box turtles carry that disease as well.

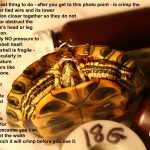

Don’t Rush Repair

Don’t be in a hurry to permanently close or seal shell fractures. Rapid closure seals in bacteria, fungi, dead tissue and foreign material. Let the turtle’s natural healing processes purge those elements first. Wound odor tells you a lot. After thoroughly cleaning the cracks (#3 below) and allowing them to dry, you can approximate the shell portions with small strips of Gorilla™ tape. Tegaderm™ and stoma adhesive patches cut to size, work well too. But leave the cracks slightly open at both ends so that they can drain. Given time, reptiles have a truly amazing powers of healing and regeneration. (read here) If necessary, you can tighten up the shell portions with wire later once the turtle has established barriers to infection.

Container Environment

Fractured turtles do best for me when I keep them in plastic storage tubs with a substrate of damp paper towels. I house fractured tortoises in dry enclosures without fine bedding that can enter or stick to moist shell wounds. They cannot escape from plastic storage vats with high slick walls. But I cover the tub with a window screen frame to keep out flies. I also place a candy making thermometer in a small beaker of water within their environment and keep the temperature at about 85 F (29 C) using a flexible base desk lamp with a 40 watt incandescent bulb:

The Procedure:

If you scroll down to the very bottom of this article, you will find a series of photographs that show the various steps in my procedure. If you enlarge them, you will find some explanatory notes. Two sliders came in the week I took those photos. So, the series represents views to two different animals. Some are just posed views – that is why you see the wires already in place. If these photos are not sufficiently self-explanatory, you can always write to me.

Be very cautious when using human hair dryers on animals. Animal dryers are specifically designed to not run as hot. Always keep your hand in the air stream, so you know when the temperature at shell level is too high. I re-swab the turtles with hydrogen peroxide solution daily until it no longer produces foam. Then I know that the wound has sealed, healing has begun, and I can seal it permanently. When the wound(s) is severe, I occasionally give these animals injections of Batryl® and cefazolin (enrofloxacin 3-5 mg/1000 gm and cefazolin, 10-20 mg/1000gm both diluted in 5 times their volume of sterile saline) under the skin above either front leg. Besides reducing the irritating effects of enrofloxacin injections, the added saline is helpful to dehydrated animals.

I am not saying that you have to or should do that. Turtles can hold their breath a long time, so I can never be sure how much of the gas enters their lungs. However, they appear to struggle less after they are placed with their nose in the cone for a while. I do not use a rebreathing, gas scavenging (gathering) system with animals this small. Anesthesia gases, like most volatiles, are not healthy for you to frequently breath. (read here) So you might want to consider if you really want to subject yourself to that risk. A little lidocaine like your dentist uses, applied to the location once drilling has begun, might be an alternative. But no one I know of has confirmed that that is effective either.

When I drill holes into a turtle shell to accommodate a length of 18 Ga wire snugly, I use 1.5 mm drill bits such as these:

I use this flexible shaft drill to create the small shell holes for the wire:

I would purchase a Foredom™ instead if I had the resources:

Between use, instruments that are not made from stainless steel get wiped down with isopropyl alcohol or placed in the oven. When the cleanliness of any metal object is in doubt, a butane lighter flame (flaming) passed over them assures that they are sterile – I do that with things like drill bits and the stainless-steel wire:

9) The flexible wire is then slowly “snugged up” – gently pulled a little on one side and then the other until the two sides of the crack fit as snugly together as possible. In numerous instances, they fit so snugly that no crack is visible to the eye. I modified a pair of hospital backhaus towel clamps which I sometimes use to maintain the shell portions in proper alignment while I am working. A drill bit nick on either side of the crack allows the towel clamp’s points to grasp the shell firmly.

10) When repair is complete, keep aquatic turtles in a container/tub lined with moist paper towels for 4–7 days. Swab off their shells with water several times a day. After that, remove the wet towels and fill with enough water to cover only their toes. I let tap water set for 48 hrs to dissipate the chlorine before using it. (That may be unnecessary as we maintained our sea turtles in 1 ppm chlorinated water for years at Sea World. My city water chlorine content is 1.5 at the rehab tap.

Tortoises need no moist towels and go back to a large leaf substrate vat 4 days later. For water turtles I gradually increase the depth of the water and add flat stones for them to haul out on. A 40-watt bulb in a desk lamp pointed at one area of the container maintains my thermometer temperature at 85 F. In my experience, these recovering turtles prefer to spend most of their time basking on the rocks rather than submerged in the water. The tub needs to be large enough for the turtles to have a temperature gradient, so they can choose the temperature that suits them best for rapid healing.

11) I am not a fan of patching aquatic turtles with fiberglass, epoxy glues or other products. They initially look good and turtles released with those patches probably do survive for a while. Sometimes I do apply a thin layer of JB weld over the repaired crack. But I know that it is no more than a temporary Band-Aid that will soon fall off. A turtle’s shell is dynamic and none of these products actually bond to living bone or scutes. Eventually, patches that don’t fall off on their own trap bacteria and rotting debris between them and the living shell. Aquatic turtles with these large defects are probably best maintained in captivity in shallow water for the rest of their lives. For large areas missing shell, plastilina makes a good temporary defect filler that can be removed now and then for examination and treatment until the area is fully filled in by mature scar tissue – as in these photos:

The same goes for turtles that have lost a front foot or leg. My experience with sea turtles that were missing front limbs is that they never adapted sufficiently to forage in the wild. Instead, they swam in tight circles that precluded purposeful feeding activities. Land tortoises seem to do considerably better long term when their cracks are closed with wire and allowed to heal before release.

This one I later repaired with wire is a Texas gopher tortoise. It had no further health issues over the year I kept it before it was finally released back to where it was found.

Here are more photos of my repair procedure:

Will Some Turtles With Shell Damage Heal On Their Own?

Yes,

This Texas Tortoise was run over by a riding lawnmower. It lost part of its shell. It has taken 5 months, but with the help of some honey, the tortoise has finally healed. Today it is being dropped off in the Laguna Atascosa dry brush country. At first, I applied the honey lightly to 4″x 4″ gauze sponges and packed the defect with those. I did not want the honey to penetrate deep into the wound. Even then, the honey prevented fly maggots from becoming established. With time, I could just smear a thin layer of honey over the shell defect. Honey has many beneficial properties that you can read about here.